James Goldman's book to Follies

bk

Broadway Legend Joined: 7/20/03

#50James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/28/17 at 6:14pm

Yes, that was my point throughout this, Hog notwithstanding. If you've only seen productions with a revised script (and most of the productions of the past twenty-something years have not used the original script, then commenting on the book is fine, as long as it's acknowledged that it really isn't the original book of Follies. And if you've only seen productions in which the director and actors don't quite make the show work, then there's that, too. And believe me, yes, there are some who saw the original and didn't like the book but I haven't met a lot of those people.

#51James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/28/17 at 6:50pm

Don't pretend like the original Follies was universally beloved. Susskind has it at 3 raves, one favorable, one mixed, and one unfavorable. Walter Kerr himself did not like the show. Here's what he wrote:

“FOLLIES” is intermissionless amd exhausting, an extravaganza that becomes tedious for two simple reasons: Its extravagances have nothing to do with its pebble of a plot; and the plot, which could be wrapped up in approximately two songs, dawdles through 22 before it declares itself done.

No one likes to dismiss the ingenuity that producerdirector Harold Prince has splattered all over the Winter Garden stage—platforms bearing jazz bands gliding in out of the dark, curtains made of candy?box lace raining down from the skies, the ghosts of showgirls past stalking in black?and?white butterfly wings through the ruins of a once?festive playhouse—but ingenuity without inspiration can quickly become wearing and we are not too long in our seats before we realize that no one on the creative staff has had an idea for the evening capable of sustaining its weight in silvered feathers.

James Goldman has done the libretto; everyone else is rather grimly chained to it. It is trivial and—for all the time it spends on its four fretting principals — unclear. An Impresario (Arnold Moss) who isn't named Ziegfeld and who is got up to look like a sinister Al Hirschfeld (impossible) has called back into his crumbling theater the available survivors of his musicals of 30—or 40 or 50—years ago.

To the reunion come longmarried Dorothy Collins and Gene Nelson, she to find once again the man she thinks she ought to have married, ho to keep a worried and still yearning eye on her. The man she thinks she ought to have married, John McMartin, is there indeed, drinking a bit too much and detesting himself for his own emotional failures; with him is his wife, Alexis Smith, svelte and poised and altogether glorious, wondering why her hands feel so empty. Thirty years earlier these four went off together cheerily after each show; can their mismatches be unscrambled, their melancholia assuaged, now?

The huge entertainment has nothing in mind but to introduce us to these disenchanted figures, let us watch them drift in and out among the other guests in groping search of one another, let us hear them state and restate in song the present temperatures of their lives (“The Road You Didn't Take,” “Too Many Mornings,” “The Right Girl,” “Could I Leave You?&rdquo![]() , and then, in a burst of red top hats and tails, puts them through a remembered Follies performance (“Loveland&rdquo

, and then, in a burst of red top hats and tails, puts them through a remembered Follies performance (“Loveland&rdquo![]() by way of exorcising their regrets.

by way of exorcising their regrets.

Continue reading the main story

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

If they are not very interesting to follow, and difficult to feel for, it is because we never do—in two hours of searching—learn much that is private about them. Why didn't Mr. McMartin marry Miss Collins in the first place? No one really says, though we see them—through youthful alter egos—skipping down iron backstage stairwells together time and again. When Miss Collins announces, at the reunion, that Mr. McMartin has asked to marry her now, has he? Or is she remembering? Or fantasizing? Skipping back and forth in time as we do, it's not easy to say. When the rainbow tormentors and the Dresden ? shepherdess chorines at last appear for a reliving of the gaudy idiocy that once passed for entertainment, what is there in the reliving that persuades the couples to accept their numbing fates and go off arm in arm as they have come? The therapy is a?clatter with fast taps, and it's fun watching Mr. Nelson appear at the top of the glistening front?curtain, slide all the way down and pop through it instantly in a blue automobile built for one, but it offers very little in the way of emotional explanation. The body of the evening lies in these interlocked lives; the keys to the locks are lost in some other theater.

The players themselves are attractive; Alexis Smith, in particular, is dazzling. Miss Smith is one of those rare creatures who, after a respectable but less than worldshaking career in films. emerges on stage as not only more animated and charming than she'd ever seemed before but also more beautiful. (She looks like the youthful Dolores Costello, since we're talking about the past anyway, only happier.) Wrapped in floor?length red—we're denied a view of her legs until 9:45, which is stingy of someone though it does do wonders for 9:45—and spotted with tiny silver stars that seem to match the corners of her eyes, she sings winningly, dances with a wink, and takes charge of her dialogue scenes (she treats each new day, she tells us, as a painter might, insisting on getting the colors right) with a lacquered authority that has crisp intelligence inside it. She does the colors right.

Mr. Nelson's one exuberant leap into space for a cartwheel across the platforms and a dizzying spin around the hand?rails—Michael Bennett has done the choreography as well as co?directing with Mr. Prince—is lithe and lively, Miss Collins does very nicely with “In Buddy's Eyes” (“On Buddy's shoulder/I won't grow older&rdquo![]() , and Mr. McMartin amusing as he sucseeds in inserting a yawn into “You were terrific” while he contemplates the woman he once so ardently seduced.

, and Mr. McMartin amusing as he sucseeds in inserting a yawn into “You were terrific” while he contemplates the woman he once so ardently seduced.

The balance of the show is composed of interruptions—tactical delays, you might call them—in the form of numbers done by oldsters (some of them not so very old). While Miss Collins is off tracking Mr. McMartin down, say, Fifi D'Orsay may appear —very briefly—to scrape her low gurgle upward against the quiver of those kinky vocal chords or Justine Johnston may be discovered, in hair red enough to shame a flame?bush, to trill an operetta melody half ? remembered from Sigmund Romberg.

Of course we are eager to show our fondness for these faces that spell dawn to us; they are not, however, terribly well introduced. It takes a very long time, at the beginning of the evening, to get them on, and we are sometimes puzzled by what are obviously intended as applause entrances for the rather disturbing reason that we don't recognize them all now. They do, however, give “Follies” such warmth as is in it. I'd say that Ethel Shutta, Mary McCarty, and Yvonne De Carlo come off best, Miss Shutta jabbing a rhythmic finger at us as she thrusts one foot forward and teaches us what it is to place a song, Miss McCarty seeming to shoulder the sky aside as she shouts, “Who's That Woman?”, Miss De Carib smokily insisting, “I'm Still Here” (“When you've been through Herbert and J. Edgar Hoover/Anything else is a laugh&rdquo![]() , though she doesn't—in all truth—lobk as though she'd been anywhere.

, though she doesn't—in all truth—lobk as though she'd been anywhere.

The fact that the musical pastiches, written to remind us of what these performers used to do, do not have any real relationship to the marital squabbles at hand—the two marriages of the evening could be dropped in toto into Mr. Prince's other musical of the moment, “Company,” without fuss or loss or even anyone's noticing it—poses a serious problem for composer Stephen Sondheim, one I do not think he has solved.

He must suggest, in all of the period interpolations and certainly in the partly parodied “Loveland” that consumes the last half hour, the beats and breaks and sassysweet syncopations of other times, other tempos. It is a kind of thing that someone like Jule Styne does beautifully, perhaps because he has a lingering love for the styles as styles. Mr. Sondheim is younger, he may he too much a man of the seventies, too present ? tense sophisticated, for that: in any case, he makes it all come out ordinary. He seems to he imitating the imitators, rather than the happy originals.

And his own inventive hands are somewhat tied by the need to fuse—in a cohesive score these not?quiteremembered echoes with the contemporary cross ? hatched love stories. He can't just split the score down the middle. But the effort to bind it up inhibits the crackling, open?ended, restlessly varied surges of sound he devised with such distinction for “Company” without earning him much in the way of pleasant nostalgia. He's caught half way, and the narrowness of the middle range grows monotonous. Even so, “Waiting for the Girls Upstairs,” with Mr. Nelson and Mr. McMartin serenading the dressing?rooms while their dates get their eyelashes off, is charming, and “I'm Still Here” is a deceptively sultry tune with a nice tough nub it.

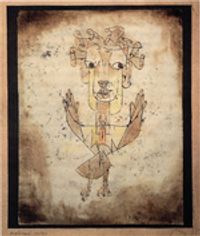

The one thing that must be said about Harold Prince is that he never cheats. To the degree that the evening is nostalgic, it offers a very cold nostalgia: The enchanting girls of yesteryear are not only older but unhappy now: the prancing shadows that we see behind them, monochromatic phantoms of their youthful selves, are pretty but their lips are made of ice; we're taking a hard look, not an indulgent one, at the naively romantic past. To let you know this before you come into the theater, Mr. Prince paints, on his posters, the granite head of a Follies girl with a crack in it; once you are inside, the proscenium is for the most part eaten away, the dilapidated rosebuds are plainly cement, and Florence Klotz's marvelously foolish headdresses — girls submerged in cotton candy, girls wearing lollipop hearts everywhere except their navels, girls topped by bird cages housing purple parrots —are not permitted to wipe away the insistence on dust.

Mr. Prince is willing to make his musicals dark, or at least caustic, with liveliness worked in only where it is legitimate; and that is courageous. Unfortunately, the liveliness here is all left?field, and the legitimacy in the love?stories that ought to give the evening its solid foothold is skimpy and sadly routine,

#52James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/28/17 at 7:01pm

Yes, Walter Kerr hated Sondheim (and Sondheim speaks of that in Look, I Made a Hat). So did Clive Barnes - who was certain that rock was the future of musical theatre. It wasn't. Frank Rich made his first waves as a reviewer seeing it and later took the job once held by Barnes and Kerr.

I don't think BK was stating that Follies was universally loved. It's common knowledge that it was incredibly divisive. Those who didn't get it were confounded and awed by the awful characters amidst the lavish and thrilling production numbers. Those who understood it so intensely they couldn't bare it ravaged it. And the people who got it and saw the humanity in it went multiple times. It was far from a critical or commercial hit, but it keeps coming back. It's still here, and so are it's detractors and adherents.

#53James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/28/17 at 7:16pm

Sally Durant Plummer said:

I don't think BK was stating that Follies was universally loved. It's common knowledge that it was incredibly divisive. Those who didn't get it were confounded and awed by the awful characters amidst the lavish and thrilling production numbers. Those who understood it so intensely they couldn't bare it ravaged it. And the people who got it and saw the humanity in it went multiple times. It was far from a critical or commercial hit, but it keeps coming back. It's still here, and so are it's detractors and adherents."

This is such a wonderful post. Spot on.

#54James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/28/17 at 7:21pm

@SDP, you came close to nailing it. And of course it comes back. Why wouldn't it? My only quibble is what you said about Barnes. He was right; he was just way ahead of his time.

#55James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/28/17 at 7:36pm

Hogan, I'd argue that the era we're in now is much more pop based than rock. Webber began as a rock musical creator, but after Evita retreated into his faux-operetta phase. There are a few exceptions, of course, but most the biggies; ie Cats, Phantom, Les Miserables weren't rock. Neither are Dear Evan Hansen or Next to Normal, though both have rock elements. Of course, pop is a rather meaningless phrase, merely meaning popular, but I think most of us can understand what I mean by differentiating pop and rock.

Besides, after Night Music (which he loved), Barnes started to like Sondheim and actually gave a very well-thought out review to Pacific Overtures (not glowing, but certainly more measured than his response to Company and Follies). Then again, he also loved Aspects of Love.

#56James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/29/17 at 8:02am

When people start talking about "pop" and "rock" as though they are inherent musical forms, rather than just instrumental arrangements, the conversation has devolved irreparably.

When it came to music, Clive Barnes was illiterate. Kurt Weill, on the other hand, said it best: "there is only good or bad music." There's absolutely no reason to believe that a score arranged for electric guitars and heavy percussion is inherently better or more successful than one scored for a full theatre orchestra.

#57James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/29/17 at 9:15am

@SDP, I understand how you are defining the terms but I think you'd agree they both bleed into each other. "Rock" is regularly used much more broadly. (One need only look at the Rock and Roll HOF to appreciate this.) I'd suggest that it mostly evolved to mean "the stuff they play on the radio" (back when that was how musical tastes were formed). And let's not forget that we are here talking about this in the context of a usage by a musical "illiterate" (see below) which I use much less negatively to mean simply that I don't think Barnes ever pretended to be an authority on the definitions of various genres of music but was speaking more broadly to mean stuff that sounds like mainstream radio rather than musical theatre or the foundation on which it had traditionally developed.

Which takes me to newintown's quite silly notions about "inherent musical forms." There are, of course, no such things for any genre. What is the inherent musical form of classical music? Silly! Barnes may or may not be unschooled in music but guess what, he wasn't reviewing music, he was reviewing a play, and because Weill indeed hit the nail on the head, the only thing that matters is how he responded to it. And the "inherently better" stuff is a non-sequitur as well as something I have never heard anyone say. How quickly you seem to have forgotten Weill! Better and more successful scores are the ones people respond to by wanting to hear.

#58James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/29/17 at 9:30am

Asking a surreal question like "What is the inherent musical form of classical music?" just further shows that you talk about music like a typical enthusiastic but uneducated dilettante (the purview for meaningless terms like "classical music" [like using "global warming" in lieu of the accurate "climate change"]). But don't be bothered by that, you're in the majority - most Americans are musically illiterate, yet believe that classes in "musical appreciation" have conveyed on them the knowledge and vocabulary to analyze music just as cogently as composers and musicians.

This is not to say that relatively unlettered aesthetic opinions on how music makes one feel have no value; they're perfectly fine. What's problematic is when that balloons into delusions of grandeur about musical knowledge.

The problem with Barnes (and his champions) is that he believed that "rock" music was one thing, and somehow an inherently different thing than any other kind of music, and that it somehow represented the future of American musical theatre. This attitude is (and always will be), that of a dilettante. Tragically, dilettantes rarely recognize the limitations of their knowledge, believing that they are, instead, experts.

If instead, he had stated that "all future American musicals should be arranged for amplified electronic guitars and basses, drum kits, electric keyboards, etc.," he would have been at least more clear and specific, but still wrong.

#59James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/29/17 at 1:45pm

@newintown notwithstanding how much you are enjoying having dilettante as your word of the day, you are wrong about just about every single thing you say, starting with me. I may not be an authority of everything but as between the two of us, I am the only expert on me, guaranteed.

The point about " classical music" is that it exhibits the same ignorance as the notion that rock is nothing more than a choice of instruments to play. That's a total joke. Talk about something that "balloons into delusions of grandeur" indeed.

Neither Barnes nor anyone I have ever read has labored under the notion that rock is one thing, any more than anyone would say that all musical theatre is the same. ever. But there is of course a past present and future in musical theatre, and we can as intelligent humans characterize the trends we see. But you go on thinking you know what you are talking about; it gives me something to laugh at.

#60James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/29/17 at 2:05pm

Well that was certainly a post devoid of actual content.

#61James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/29/17 at 3:16pm

I suppose that one could trivialize the tendency to separate music into genres but it would seem odd to me to think of Beethoven's "Symphony No. 5 In C Minor" as equivalent to, say, Ariana Grande's "Into You" (more accurately, Ariana Grande, Savan Kotecha, Alexander Kronlund, Max Martin, and Ilya Salmanzadeh's "Into You" as made famous by Ariana Grande). Not to say one is intrinsically better than the other - that comes down to a matter of personal taste and opinion. One may be more highly regarded critically, but as Sondheim goes on about at length in Look, I Made a Hat, the music industry is one of the only industries where critics are not experts in their subject. So, at best, The New York Times (or whatever it's equivalent) review is nothing more than a personal assessment paraded as fact - something most of us involved in this board understand. However, it can be stated as fact that one piece is more complex than the other. One composer is interested in experimenting with form and tonality, whereas the other is following the general form and tonal use of mainstream pop songs. I suppose one could argue that a composer like Mozart, who more strictly adhered to the sonata form and who, I assume (based on my rather limited knowledge of musical culture in the eighteenth century), wanted a "popular" success with his piano concertos is like Grande, who (I assume) wanted a popular success with "Into You". You could even go so far as to state that the tracks on Grande's album "Dangerous Woman" are the modern equivalents to different movements in symphonic works that (hopefully) create a cohesive whole.

But isn't it just easier, and more helpful, to recognize that Beethoven and Mozart are creating different types of music than Grande? It is my impression that genres of music help not only listeners find works that they are drawn to, due to similarities to other music they like, but also help people compare music of like work - after all, how can one compare a Beethoven symphony with the album "Dangerous Woman" when they are so different? Also, forms such as sonatas, concertos, ballet suites, opera, art songs, and music theatre are so different from each other - all having different subgenres within them, that isn't it helpful to be able to label them? I know "labeling" is a dirty word to some, who feel that it leads to mindless conformity, but I see at least some sense to it.

Back to the more direct question at hand: yes, I think pop and rock do lie closer to each other than a symphony and a 2016 "pop" album. And yes, the word "pop" is indeed arbitrary and was applied to both "With the Beetles" and "The Barbra Streisand Album" back in 1963 - two very different styles. But by the same token, the score of "Hair" and "Promises, Promises" are so different from "Dear Even Hansen" or "Hamilton" that I find it impossible to believe that was what Barnes was professing was the future. If you look at his statement simply as "the popular music of the time is the future of musical theatre" then he is not wrong, but with shows like "Fun Home" and "The Bridges of Madison County" winning the Tony Award for best score fairly recently, the pop/rock (whatever term you want to use) wave hasn't totally taken wing as, say, the 32 bar song (another arbitrary form) kept hold in the first half of the twentieth century (with a few exceptions, of course).

To take it a step farther, the scores to "Evita", "Phantom of the Opera", or even "Les Miserables" may have pop elements, but they didn't sound like something playing on the radio in the late 70s and 80s. In fact, the scores that sound (and have passed) as radio pop songs are the ones that generally fail as theatre songs. Take "This Is the Moment" from Jekyll and Hyde: as popular a song as can be said for Taylor Swift or Katy Perry now. Played at the Olympics and the 1996 DNC, the show it was in failed to make any money twice on Broadway. Musical theatre is always about characters, at least since 1943, and say what you will about the lyrics to Webber's shows, but "Evita", "Phantom", and even "Cats" have songs that were written for characters (yes, even the poetically nonsensical "Memory"![]() . Sure, they're much more generic and vague than Sondheim, but you can tell they fit. With "This Is the Moment" any character in any number of situations could sing that song, or "Someone Like You" or "A New Life" (the score's worst offender). It's very difficult for popular songs to organically work in theatre (look at jukebox musicals), and that's why even the generic and vague "Dear Evan Hansen" isn't true pop, at least as defined by today's radio or iTunes charts. In fact, a song like "So Big / So Small" is so specific that you gain much insight to the character from it. It is rare that 2017 pop songs capture that sense of specificity because the largest number of people possible are supposed to relate to it. Even in the phenomenon "Hamilton", which uses a huge range of pop, hip-hop, and rap in its score, there is the beautiful "Burn", which is, essentially, a traditional musical theatre song. Ditto for "I'm Not That Girl" in Wicked.

. Sure, they're much more generic and vague than Sondheim, but you can tell they fit. With "This Is the Moment" any character in any number of situations could sing that song, or "Someone Like You" or "A New Life" (the score's worst offender). It's very difficult for popular songs to organically work in theatre (look at jukebox musicals), and that's why even the generic and vague "Dear Evan Hansen" isn't true pop, at least as defined by today's radio or iTunes charts. In fact, a song like "So Big / So Small" is so specific that you gain much insight to the character from it. It is rare that 2017 pop songs capture that sense of specificity because the largest number of people possible are supposed to relate to it. Even in the phenomenon "Hamilton", which uses a huge range of pop, hip-hop, and rap in its score, there is the beautiful "Burn", which is, essentially, a traditional musical theatre song. Ditto for "I'm Not That Girl" in Wicked.

So the future of musical theatre? Perhaps. But I don't see golden age forms and styles being forgotten anytime soon. In fact, I see new musical languages being created. Mostly on the fringe of the mainstream musical scene, but some that gained traction. Just look at "The Light In the Piazza", "Caroline, or Change", "Fun Home", "The Wild Party" or "Marie Christine" to name a few (mostly unsuccessful, in terms of commerical success) Broadway offerings. I can't tell if these types of scores will ever become truly popular, but it's interesting to see theatre scores more removed from popular music than the aforementioned "Evan Hansen". Theatre is always reinventing itself. I wonder where it will go.

#62James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/29/17 at 3:40pm

Sally Durant Plummer, that's a much more detailed and thoughtful post about music that we usually find on this board, and I thank you enormously for it.

#63James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/30/17 at 1:44am

The original book of FOLLIES, more than anything, was uncompromising- it didn't "play down" to it's audience. It was also as impressionistic, in its way, as Boris Aronson's original scenic design. It shouldn't be taken as a literal party any more than the set should be seen as a literal theatre. The problem with later versions of the book was that Goldman tried to make it more "real" as the productions became more "real" (less Hal Prince). I saw the original production and I performed in a production in 1976 with the original book before the later "improvements" started creeping in. Believe me, the original book works. I've often said that FOLLIES has become our generation's SHOW BOAT, getting softer and less biting as it grows older. Too bad.

#64James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/30/17 at 2:13am

Great post, SDP. I think the "future" question is a complicated one because we are talking about a multi-headed beast when we talk about musical theatre. Among art forms, it is really the only one (I think) that plays two ends against the middle. Musicals are inextricably tied to Broadway, and Broadway is inextricably tied to commerce. But we also have non-profit musicals that are inextricably tied to art and that manage (fitfully, with rare exceptions) to find their way onto the main stem. There is no such thing as commercial opera, ballet, classical music (interestingly, placed in a separate genre from Ms. Grande et al), etc. Is there are other 2 headed beast?

I raise this because, logically, to me at least, Broadway musicals don't really make sense based on music that is not popular (and that word allows us to sidestep the rock/pop/hiphop/etc etc etc stuff). For a LONG time, Broadway musicals didn't make sense because they kept trying to fit square pegs in round holes. (It was not always thus, of course.) And now we seem to have finally emerged from what I would call a detour. Look at the new commercial musicals that succeed: count how many fit comfortably in an old school musical theatre genre. Then count how many of the "art" musicals succeed. I think we know more about the future than we think.

#65James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/30/17 at 3:16am

BakerWilliams said: "Don't pretend like the original Follies was universally beloved. Susskind has it at 3 raves, one favorable, one mixed, and one unfavorable. Walter Kerr himself did not like the show....

"

Walter Kerr now posts here under the hat "After Eight".

***

The first paragraph of Kerr's review should be enough to demonstrate what was going on. Kerr complains that the "plot is thin". Despite the raves for COMPANY, Broadway critics were still getting used to the idea that a musical might not have a conventional plot. (Just as Barnes was still trying to understand how a Broadway musical could have music that wasn't AM-radio "popular".) Some in the audience agreed, but I first saw the show with theater full of Saturday matinee ladies--"I actually saw Ethel Shutta in the ZIEGFELD FOLLIES" was overheard. They didn't seem confused so much as dazzled.

#66James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/30/17 at 3:30am

HogansHero said: "@SDP, you came close to nailing it. And of course it comes back. Why wouldn't it? My only quibble is what you said about Barnes. He was right; he was just way ahead of his time.

"

I'm sure you know Barnes was an idiot outside the classical dance world. And was he right in the end? Did Broadway become more pop/rock or did pop music return to something closer to theater music? I realize the Street now lies in the shadow of the Great Hip Hop Musical, but Broadway has featured patter songs for over a century and a half. And listening to HAMILTON the other day I was struck by how much of the score is quite melodic.

***

Sally, you said this better than I. But are you sure Barnes hated COMPANY. I think my commercial copy quotes him as praising it as a fresh new direction in musical theater. (As you'll recall, Barnes was nothing if not unpredictable.)

#67James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/30/17 at 3:48am

justoldbill said: "The original book of FOLLIES, more than anything, was uncompromising- it didn't "play down" to it's audience. It was also as impressionistic, in its way, as Boris Aronson's original scenic design. It shouldn't be taken as a literal party any more than the set should be seen as a literal theatre. The problem with later versions of the book was that Goldman tried to make it more "real" as the productions became more "real" (less Hal Prince). I saw the original production and I performed in a production in 1976 with the original book before the later "improvements" started creeping in. Believe me, the original book works. I've often said that FOLLIES has become our generation's SHOW BOAT, getting softer and less biting as it grows older. Too bad.

"

Thank you. Without your personal experience as an actor, I was thinking along similar lines the other night. I was listening to the 2011 revival, which includes quite a bit of dialogue. And it struck me that if you took the music and rhyme out of "I'm Still Here" and recited it as prose, it would sound entirely compatible with some of the speeches from the book.

I think people are used to sung-through musicals or the Hammerstein style of carefully building the emotions in the dialogue until characters must burst into song.

Goldman writes in a more epigrammatic style. (He does so in THE LION IN WINTER, too.) Some spectators may find it jarring or ham-fisted, but it's actually quite consistent with the score.

And of course you are right that none of it is supposed to realistic. God forbid!

After Eight

Broadway Legend Joined: 6/5/09

#68James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/30/17 at 5:55am

GavestonPS wrote: "Goldman writes in a more epigrammatic style. (He does so in THE LION IN WINTER, too.) Some spectators may find it jarring or ham-fisted, but it's actually quite consistent with the score."

Which is itself jarring and ham-fisted.

Perhaps the score is as much to blame as the book for the show's (repeated) failure. It doesn't exactly fall pleasantly on the ears.

The tendency is to dismiss audiences' and critics' rejection of the show as being due to some failings on their part. It isn't. It's due to the show's failings.

After Eight

Broadway Legend Joined: 6/5/09

#69James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/30/17 at 6:29am

Justoodbill wrote: "The original book of FOLLIES, more than anything, was uncompromising- it didn't "play down" to it's audience."

i find that this kind of statement is simply a way of rationalizing a show's failure and deflecting blame for a show's failings on the audience, It's also not a little offensive to shows that have --- deservedly --- known success,

Were The King and I, My Fair Lady, Hello, Dolly!, Fiddler on the Roof, Phantom, The Lion King "compromising?" Did they "play down" to their audience? Is that why audiences embraced them? And what about Cabaret or Chicago? How "compromising" were they?

It's not that Follies was too good for the audience. It wasn't good enough.

After Eight

Broadway Legend Joined: 6/5/09

#70James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/30/17 at 6:35am

Bravo, Walter Kerr. A great critic, and wholly deserving of a theatre bearing his name.

#71James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/30/17 at 8:21am

What I really love about that original book is the way the original cast read the lines in subtle and revelatory ways.

For instance, when Sally responds to Phyllis' snarking with "I'm sorry, Phyl, I don't want to fight with you. I don't have to," Dorothy Collins delivered it slowly, calmly, warmly, with a genuine smile in her voice. All her Sally cares about is seeing Ben, and she really believes that Ben will be hers before the night is over. She barely registers Phyllis' existence. In every production I've seen since, the actresses playing Sally have barked that line, as though they really DO want to fight. It's the stuff of TV acting - read the words once, and then make the most obvious choice with them. But that original cast really knew how to get under that dialogue and work extra meaning.

#72James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/30/17 at 9:02am

That was probably Bernadette's worst read line. It was truly puzzling.

#73James Goldman's book to Follies

Posted: 8/30/17 at 1:04pm

GavestonPS said: "Did Broadway become more pop/rock or did pop music return to something closer to theater music? I realize the Street now lies in the shadow of the Great Hip Hop Musical, but Broadway has featured patter songs for over a century and a half. And listening to HAMILTONthe other day I was struck by how much of the score is quite melodic."

First of all, I have no idea what melodic has to do with this. Rock and pop have always been filled with melody. Secondly, I'd say the answer is yes we now have a ton of pop/rock on Broadway, and no pop/rock has not returned to something closer to theatre music. Aside from the fact that pop/rock is about as far from a monolith as I can imagine, it's just demonstrably untrue, even assuming (maybe not a bad idea) that we could settle on the defining characteristics of theatre music in the first instance.

Videos